|

|

Common

characteristics

- These are the common characteristics of endemic dimorphic

mycoses:

They cause community acquired infections and are capable of causing

systemic disease in immune-normal and immunocompromised humans and

animals

- The mold forms occur in soil or plant matter in certain

geographic areas

- Each etiologic agent is morphologically distinct.

- They all exhibit dimorphism: def: existence is in two distinct

forms:

- The environmental form is as soil-dwelling mold.

- In the host the conidia germinate and undergo

temperature-sensitive conversion to the tissue form as either

yeast forms, fission yeast, or endosporulating spherules.

- Transmission is via inhalation of conidia (spores) from the

environment

- They are not communicable among people (with rare

exceptions).

- Inhalation of conidia initiates a pulmonary infection.

- The conidia germinate and convert to the tissue form (see

above: dimorphism)

- Depending on the inhaled dose, immune, and endocrine status

of the host: fungi may then either be phagocytosed, walled off

in granulomas, or are killed (most patients), or go on to

produce pneumonia and, in a small fraction of patients,

disseminate to other organs, including skin.

- Host response is T-cell mediated, isolating the fungi in

granulomas. i.e.: fungi are surrounded by macrophages

which may combine to form multinucleate giant cells

- Subclinical exposure resulting in self-limited infection

- Community acquired pneumonia

- Chronic lung disease

- Extra pulmonary dissemination

List of the Endemic Dimorphic Mycoses

Blastomycosis

Coccidioidomycosis

Histoplasmosis

Paracoccidioidomycosis

(the above fungi are phylogenetically related within the family

Onygenaceae)

Sporotrichosis

Talaromycosis (formerly Penicilliosis)

BLASTOMYCOSIS (Blastomyces

dermatitidis)

Disease Definition

Blastomycosis is a slowly progressing chronic pyo-granulomatous

disease of humans and dogs, most often presenting in a pulmonary

and/or cutaneous clinical form. The respiratory route is the most

important for infection via inhaling conidia or mycelial elements

from aerosolized soil, or from vegetative material.

- Blastomycosis is a rural disease but isolation of the

causative agent from the environment is uncommon.

- The patient presents with respiratory symptoms, loss of

appetite, weight loss, fever, productive cough, and night

sweats.

- Symptomatic disease may be present in less than half of

infected persons; others may have a "flu-like" response to

infection.

- Cutaneous lesions are most often secondary to hematogenous

spread. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis can occur but is

uncommon (see below Clinical Forms).

- Pulmonary and skin (fig 1) involvement are most common, but

bone, prostate are other sites of dissemination also including

other organs.

- Blastomycosis is correctly suspected in only a small

percentage of patients at the first clinical evaluation.

- The differential diagnosis includes bacterial pneumonia,

cancer, or tuberculosis.

Fig. 1. Skin lesion, face, blastomycosis. This 54 y.o. man was seen

in the early 1960’s. He worked in a print shop in an Atlanta suburb.

It is unlikely that he traveled out of state. He had pulmonary

blastomycosis about 2 or 3 y before the current admission. When skin

lesions appeared he was referred to the Medical College of Georgia,

where he received a course of Amphotericin B.

Fig. 1. Skin lesion, face, blastomycosis. This 54 y.o. man was seen

in the early 1960’s. He worked in a print shop in an Atlanta suburb.

It is unlikely that he traveled out of state. He had pulmonary

blastomycosis about 2 or 3 y before the current admission. When skin

lesions appeared he was referred to the Medical College of Georgia,

where he received a course of Amphotericin B.

Photo credit: Dr.

Arthur F. DiSalvo

Etiologic agent

Blastomyces dermatitidis is a dimorphic fungus existing as a mold

form in soil or vegetative debris and, following inhalation of the

conidia or mycelial elements, changes to a monopolar budding yeast

form. The yeast form may also be demonstrated in the lab by

cultivation at 37oC.

Two evolutionary independent lineages of Blastomyces species were

discovered by applying multilocus sequence typing using 7 nuclear

loci. A genetically divergent clade within B. dermatitidis was

described as a new species, B. gilchristii (Brown et al., 2013).

Differences in geographic distribution and virulence are discussed

in Geographic Distribution (below).

Diagnosis

To make the specific diagnosis, the physician must be

aware of blastomycosis. Sputum sent to the lab for "culture" may not

grow unless the lab is alerted to look for fungi, generally, or

specifically for Blastomyces. In that case the lab will use fungal

media for isolation (see Laboratory, below). A typical cutaneous

lesion shows central healing with microabscesses at the periphery.

B. dermatitidis yeast forms can frequently be demonstrated in a KOH

prep of pus from such a lesion.

Risk factors

Blastomycosis is most often a rural disease. Blastomyces spp.

infect immune-normal as well as immunocompromised people who become

infected because, through recreation or occupation, they disturb the

environment: collecting firewood, tearing down old buildings.

Geographic Distribution and

Ecologic Niche

Blastomycosis occurs in eastern North America (fig 2). It is endemic

in southern and SE states that border the Ohio River and Mississippi

River valleys of the U.S., the midwestern states, and Canadian

provinces bordering the Great Lakes and the Saint Lawrence River.

Most reported cases occurred in Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi,

North Carolina, Tennessee, Louisiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin. The

disease is hyperendemic in north-central Wisconsin and the northern

region of Ontario, Canada.

The ecologic niche where the sexual reproduction, growth, and

dispersal of B. dermatitidis and B. gilchristii occur is linked to

freshwater systems.

B. dermatitidis isolates were recovered from human patients

and canines in areas throughout the endemic region in North America,

whereas B. gilchristii strains are restricted to Canada and some

northern U.S. states. Both species are associated with major

freshwater drainage basins.

B. dermatitidis populations are found in the:

- Nelson River drainage basin

- St. Lawrence River and northeast Atlantic Ocean Seaboard

drainage basins

- Mississippi River System drainage basin

- Gulf of Mexico Seaboard and southeast Atlantic Ocean

Seaboard drainage basins.

B. gilchristii populations occur among the more northerly

drainage basins only.

Fig. 2. Areas endemic for blastomycosis in the United States

extending into Canada.

Fig. 2. Areas endemic for blastomycosis in the United States

extending into Canada.

Source: CDC

Blastomycosis outside

the U.S.

Authentic cases of blastomycosis also occur in Africa,

specifically South Africa and Zimbabwe. Infections have also been

reported in India. Such reports are to be viewed with caution

because physicians, unfamiliar with the disease, may invoke a wrong

diagnosis. B. dermatitidis can be transferred via fomites

from a known endemic area to another area where the disease may be

recognized. Blastomycosis may be recur because of endogenous

reactivation after a person has relocated.

Ecologic niche

The ecologic niche of B. dermatitidis is wet soil containing

animal droppings, rotting wood, other decaying vegetable matter.

Disruption of these environments containing microfoci of B. dermatitidis mycelia releases infectious conidia, which may be

inhaled by a susceptible host.

Clinical Forms

Pulmonary blastomycosis is seen in four broad categories:

• Asymptomatic, with only serologic evidence of prior infection or

granulomas

• Acute localized pneumonia

• Severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

• Subacute to chronic infiltrates and/or cavitary

disease

Chest X-ray (fig 3) shows obvious pulmonary disease.

Primary cutaneous blastomycosis caused by traumatic inoculation with

the organism, is uncommon, with fewer than 50 reported cases (Ladizinski

et al 2018) e.g.: among laboratory or morgue workers, dog handlers

after a bite or scratch, tree bark trauma, sawhorse-related injury,

grain elevator door–related trauma.

Fig. 3. Blastomycosis: Chest X-ray demonstrates lung infiltrates due

to blastomycosis.

Fig. 3. Blastomycosis: Chest X-ray demonstrates lung infiltrates due

to blastomycosis.

Source: CDC Public Health Image Library #5801 Dr.

Hardin

Laboratory

If there are skin lesions, send skin scrapings or pus. If there is

pulmonary involvement, send sputum or bronchial washings. Other

specimens include biopsy material and urine. Occasionally, the

organism can be isolated from urine as it often infects the

prostate. A pus specimen from a skin lesion may be obtained by

nicking the top of a microabscess with a scalpel, obtaining the

purulent material and making a KOH prep for microscopic exam. The

yeast form has a characteristic double contoured wall with a single

bud on a wide base (figs 4 - 5).

Specimens should be seeded to SDA or inhibitory mold agar. Addition

of cycloheximide and chloramphenicol will inhibit bacteria and

rapid-growing fungal saprobes. Media with and without antibiotics

are preferred. For tissue specimens, an enriched medium like brain

heart infusion + 5% sheep RBC and antibiotics is recommended.

After planting the specimen to an agar slant or plate, incubation is

conducted at both 37 o C and at 25 o C because, B. dermatitidis is

dimorphic. Culture of B. dermatitidis takes 2 to 3 wks to

grow at 25 oC.

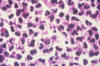

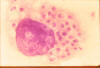

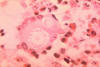

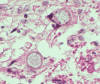

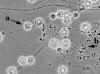

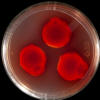

Fig. 4. Histopathology of a blastomycosis skin lesion. Budding yeast

of Blastomyces dermatitidis surrounded by neutrophils. Multiple

nuclei are visible in the yeast form.

Fig. 4. Histopathology of a blastomycosis skin lesion. Budding yeast

of Blastomyces dermatitidis surrounded by neutrophils. Multiple

nuclei are visible in the yeast form.

Source: Dr. Edwin P. Ewing,

Jr., CDC Public Health Image Library (PHIL) #491.

Fig. 5. Photomicrograph of a smear specimen from a foot lesion in a

case of blastomycosis. B. dermatitidis yeast cell is undergoing

broad-base budding.

Fig. 5. Photomicrograph of a smear specimen from a foot lesion in a

case of blastomycosis. B. dermatitidis yeast cell is undergoing

broad-base budding.

Source: #489 CDC PHIL

Colony morphology

A white, cottony mycelium on Sabouraud -dextrose agar.

Microscopic morphology. The conidia, are evident but the mold

cannot be identified by its conidia formation alone because

other fungal saprobes have similar conidia morphology.

At 37 degrees C the yeast form grows in about 7-10 d as a

buttery-like, soft colony with a tan color. Microscopically,

typical yeast forms are 12-15 microns in diameter with a thick cell

wall and a single bud with a characteristic wide base.

Laboratory conversion of forms of

growth

The yeast will convert

to the mycelial form when incubated at 25 degrees C, taking from 3 - 4

d or up to a few wks. Similarly, mycelial growth can be

converted to yeast form when incubated at 37 degrees C. Now it is

possible to take the mycelial growth (which is the easier to

grow), and confirm the isolate with a DNA probe in a matter of

h.

Histopathology

B. dermatitidis produces both a granulomatous and

suppurative tissue reaction.

Serology

Immunodiffusion test (precipitins in agar gel). The active

antigen is “A”, or “BAD-1”, an adhesin. Antibody concentrations

require 2 to 3 weeks to be high enough to cause a positive

precipitin reaction. This test is positive in about 80% of the

patients with blastomycosis. When positive, there is close to

100% specificity.

Complement fixation (CF) test

This test requires 2 to 3 mo after the onset of disease to

develop detectable antibodies. Besides this long delay another

disadvantage of the CF is that it cross-reacts with other fungal

infections (coccidioidomycosis and histoplasmosis). The

advantage is that it is a quantitative test so the patient's

response to therapy can be monitored over time.

Enzyme Immunoassay for antibodies

Microtitration plate EIA detects antibodies to BAD-1, a surface

antigen of B. dermatitidis (Richer et al, 2014). This assay is

more sensitive than the agar immunodiffusion test and is highly

specific for B. dermatitidis, with no cross-reaction in serum

from patients with histoplasmosis. The test is not, as yet,

commercially available.

Antigenuria

The urine of patients with blastomycosis may contain

cross-reactive or shared antigens with H. capsulatum. Patients

with multisystem disseminated disease have a high rate of

positive urine antigen detectable by EIA. So it has high

sensitivity but low specificity. Antigenuria was detected in

89.9% of patients with culture- or histopathology-proven

blastomycosis (Connolly et al, 2012). Specificity was 99.0% in

patients with non-fungal infections and healthy subjects, but

cross-reactions occurred in 95.6% of patients with

histoplasmosis.

Therapy (for

complete guideline see Chapman et al., 2008)

- Mild to moderate pulmonary or disseminated

blastomycosis: Itraconazole 200 mg oral tablets once or 2x/d for

6-12 mo.

- Moderately severe pulmonary or disseminated (but without CNS

involvement). Amphotericin B (AmB) or lipid AmB for 1-2 wks,

followed by itraconazole for 6-12 mo.

- CNS blastomycosis: lipid AmB for 4-6 wks, then oral azole

for at least 1 y (itraconazole, fluconazole or voriconazole).

- Immunosuppressed patients: Induction therapy with AmB or

lipid AmB followed by itraconazole for 12 mo. Therapy to

continue beyond 1 y if immunocompetence does not improve.

COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

Introduction

Disease Definition

Coccidioidomycosis (a.k.a.:“Valley Fever”, “desert rheumatism”,

“cocci”) is primarily a pulmonary disease classed as a type of

community acquired pneumonia. It is caused by the inhalation of

airborne arthroconidia of the dimorphic fungus Coccidioides, found

in soil of the endemic areas in the climate of the lower Sonoran

life zone. That includes the central valley of California (including

Fresno, Kern, and King counties) and the Arizona endemic area

including Maricopa County (Phoenix) and Pima County (Tucson),

overlapping the border into NW Mexico. It is a New World disease.

Most people (60%) have no or mild flu-like symptoms and do not see a

doctor. Symptoms, when present, are fatigue, cough, fever, night

sweats, loss of appetite, chest pain, muscle and joint aches

particularly of ankles and knees. There may be a rash resembling

measles or hives but more often as tender red bumps on the shins or

forearms.

Range of Valley Fever Cases:

- Mild - 60%, not requiring medical attention.

- Moderate - 30%, requires medical attention

- Complications - 5% to 10% (see Clinical Forms)

- Fatal - less than 1%

After recovery most people will have life-long immunity.

Coccidioidomycosis is not communicable.

Diagnosis

Physical diagnosis consists of checking for fatigue, respiratory,

musculoskeletal symptoms, and skin rashes. History of residence in

or recent travel to the endemic areas is queried*. If the answers to

the above questions are positive then coccidioidomycosis is in the

differential and pertinent tests are requested. The first

presumptive test is an EIA screening test for IgM or IgG

coccidioidal antibodies. If positive, risk factors and complications

are queried. A negative test does not exclude coccidioidomycosis. If

a follow-up tests remain negative over 2 mo the probability of

coccidioidomycosis is lower. Additional confirmatory lab tests,

including culture of the pathogen, are discussed under “Laboratory”,

below.

*Uncommonly, handling goods originating in the endemic areas.

Etiologic Agents

Coccidioides immitis (California); C. posadasii (Arizona, Mexico,

microfoci in Latin America). Soil dwelling mold, rapid growing,

fluffy or powdery colony (buff, yellow or tan). Hyphae fragment into

arthroconidia: They are the infectious particles, dangerous to

inhale!

Life cycle of Coccidioides spp. (fig. 6)

Coccidioides is a dimorphic

fungus with two distinct forms. 1) Environmental form: the

infectious propagules are arthroconidia formed by fragmentation of

hyphae in soil. 2) The tissue form consists of endosporulating

spherules.

Fig.6. Biology of coccidioidomycosis .

Fig.6. Biology of coccidioidomycosis .

Source: CDC

Geographic Distribution

The geographic distribution of Coccidioides spp. is the Sonoran

desert, which includes the deserts of the Southwest (California,

Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and Texas) and northern Mexico

(fig. 6). It is also found in small foci in Central and South

America. The climate is the Lower Sonoran life zone consisting of

arid and semi-arid desert and desert grassland with hot summers and

a few winter freezes, low altitude, and alkaline soil.

Characteristic plants are creosote bush (Larrea tridentata), Joshua

tree (Yucca brevifolia), and cacti. Other typical plants include

Black Grama (Bouteloua eriopoda), Lechuguilla (Agave lechuguilla),

Tarbush (Flourensia cernua), and Ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens).

Some typical mammals include Merriam's Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys

merriami) and Mearns Grasshopper Mouse (Onychomys arenicola). Rain

storms occur in “Monsoon” season, in July – September.

Ecologic Niche

Desert soil, pottery, archaeologic middens, cotton grown in the

endemic areas, and rodent burrows all can harbor Coccidioides spp.

mold forms. Spores, arthroconidia, of the fungus are readily

airborne, can be carried by the wind, spreading hundreds of miles in

storms. In 1978, cases were seen in Sacramento 500 miles north of

the endemic area from a dust storm in southern California.

Epidemiology

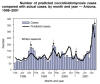

Seasonality in the Arizona endemic area (fig. 7) (Comrie 2005,

Komatsu et al., 2003). Seasonal patterns in the desert southwest

U.S. coincide with peaks and off-peak for coccidioidomycosis.

Arizona experiences about 12.5 inches of annual rainfall but it

follows a bimodal seasonality. Winter has wet weather

(December-March), followed by the driest time of year: foresummer

(May-July), monsoon season of wet weather (August-September), fall

is dry (October-December). Coccidioidomycosis seasons for exposure

consist of a winter decrease (January through April), a foresummer

peak (May –July), a monsoon decrease (August-September), and a fall

peak (October-December).

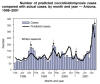

Fig. 7. Seasonality of coccidioidomycosis in the AZ endemic area

(see text for details)

Fig. 7. Seasonality of coccidioidomycosis in the AZ endemic area

(see text for details)

Source: Komatsu et al, 2003 CDC

Monthly coccidioidomycosis rates are consistent with increased dust

exposure leading to increased disease incidence. Precipitation

during the foresummer is most favorable for Coccidioides growth at a

time when the soil is desiccated and vegetation is dormant. Fungal

spores produced after a wet period in the foresummer may remain

viable in the soil for years.

Seasonality in the California endemic area. The center is

Bakersfield. Wettest mo are Jan-March. May –Sept are dry, with

precipitation increasing from October to December. Annual cycles of

valley fever incidence and climate variables in San Joaquin Valley,

California are shown in fig 8 (Gorris et al., 2017).

Climate factors other than seasonality influence coccidioidomycosis:

An outbreak of coccidioidomycosis occurred after the 1994 earthquake

in Northridge, California with an attack rate of 30 cases per

100,000 inhabitants. Being in a dust cloud increased the risk of

diagnosis (Schneider et al., 1997). A dust storm originated near the

Tehachapi mountains in southern California (Pappagianis and

Einstein, 1978). This ground level windstorm of December 20, 1977

carried heavy quantities of dust containing Coccidioides

arthroconidia to the north and west of Kern County in the San

Joaquin valley, CA. In the following 5 mo new coccidioidomycosis

cases occurred in northern and coastal areas of San Francisco,

Sacramento, the east bay, and Santa Clara and Monterey counties. By

the end of the May 1978, more than 532 new cases of

coccidioidomycosis were confirmed by the California State Department

of Health.

Fig. 8. Mean annual cycles of valley fever incidence and climate

variables in San Joaquin Valley, California. (a) Monthly valley

fever incidence, (b) surface air temperature, (c) monthly

precipitation, (d) avg. soil moisture in the top 10 cm, (e) surface

dust conc. Incidence reaches seasonal maxima following periods of

low environmental moisture. Error bars are s.d. of mo avg between

counties (Gorris et al., 2017).

Fig. 8. Mean annual cycles of valley fever incidence and climate

variables in San Joaquin Valley, California. (a) Monthly valley

fever incidence, (b) surface air temperature, (c) monthly

precipitation, (d) avg. soil moisture in the top 10 cm, (e) surface

dust conc. Incidence reaches seasonal maxima following periods of

low environmental moisture. Error bars are s.d. of mo avg between

counties (Gorris et al., 2017).

Used with permission of a Creative Commons license for educational

purpose

Incidence and Prevalence

California endemic area

From 1995, when coccidioidomycosis became an individually

reportable disease in California, to 2009, annual incidence

rates ranged from 1.9 to 8.4 per 100,000, followed by a

substantial increase to 11.9 per 100,000 in 2010 and a peak of

13.8 per 100,000 in 2011. Annual rates decreased during

2012–2014, but increased in 2016 to 13.7 per 100,000, with 5,372

reported cases, the highest annual number of cases in California

recorded to date (Cooksey et al., 2017).

Arizona endemic area

In the same period as the above report in the Arizona endemic area

incidence rates rose from 36.1 per 100, 000 in 1999 to 255.8 per

100,000 in 2011 and in 2016 the rate was 89.3 per 100,000 with

6101 reported cases (Arizona Department of Health Services,

2017)

Occupational and

recreational risk factors for coccidioidomycosis

(Freedman et al., 2018).

Human activity in the California and Arizona endemic areas are

associated with outbreaks of coccidioidomycosis. Among these are

military maneuvers, construction, archeologic digs, including

disruption of Native American sites.

Outbreaks have occurred among persons incarcerated in the endemic

areas who often had no prior exposure to coccidioidomycosis, were

immunologically naïve, and thus at greater risk. To minimize

illness, inmates who are immunosuppressed, are African-American, or

Filipino, or have diabetes mellitus are no longer housed in several

prisons in California’s Central Valley.

Cases remote from the endemic area are usually in patients who have

visited an endemic area and brought back pottery, or blankets

purchased from a dusty roadside stand, or in Navy and Air Force

personnel who were exposed when they were stationed in the endemic

area. An example is of cases occurring in cotton mills in Burlington

and Charlotte, N.C. when cotton, grown in the desert of the

southwest U.S, was contaminated with fungus spores and mill workers

inhaled them while handling the raw cotton.

Risk Groups/Factors

Life-long immunity usually follows infection with Coccidioides

spp.

Risk factors for

Coccidioidomycosis

Risk of disseminated coccidioidomycosis linked to ethnicity.

Single-site and multisite disease accounted for 86% of

extrapulmonary Coccidioides infections in African-Americans and 91%

in Asians but for only 56% in whites and 52% in Hispanics (Odio et

al., 2017). Further, African-Americans accounted for about one-third

of single-site and multi-site infections while making up only 6% of

the population in coccidioidomycosis-endemic areas. In contrast,

only 10% of patients with single-site and multi-site disease were

Hispanic, even though Hispanics are 35% of the population in those

areas.

Exogenous immunosuppression is a more significant factor than

intrinsic racial/ethnic variation in host defense. Future studies

with known ancestral markers will help identify associations between

coccidioidomycosis and race/ethnicity.

Occupational risk factors

Workers in endemic areas at increased risk for

coccidioidomycosis include those employed in agriculture,

construction, and archeologic work, military personnel, and

those in mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction

industries (de Perio et al 2019). The common theme is

disturbance of the soil, or dust-disturbing winds. Clusters of

infections also occurred among employees and inmates at state

prisons in endemic areas. Newer industries such as solar farms

also expose workers. Coccidioidomycosis is also known as a

troubling risk in clinical laboratories.

Transmission

Inhalation of Coccidioides spores (arthroconidia)

carried in dust particles from the soil by the wind when the

desert soil is disturbed in the two defined endemic areas:

Central Valley of California and in Arizona .

Determinants of Pathogenicity

Dimorphism. The organism follows the saprobic cycle in the soil

and the parasitic cycle in humans and animals. The saprobic

cycle starts in soil with arthroconidia that develop into

mycelium. The mycelium then matures and forms alternating

arthroconidia which, when released, germinate back into mycelia

(fig 9). The parasitic cycle involves the inhalation of the

arthroconidia by animals which then form spherules filled with

endospores (fig 10).

Fig. 9. Coccidioides alternating arthroconidia; these are the

infectious propagules, dangerous to inhale.

Fig. 9. Coccidioides alternating arthroconidia; these are the

infectious propagules, dangerous to inhale.

Source: Dr. Arthur F. DiSalvo

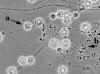

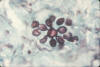

Fig. 10. Smear of exudate showing spherules of Coccidioides immitis.

Experimental infection of mouse with soil sample.

Fig. 10. Smear of exudate showing spherules of Coccidioides immitis.

Experimental infection of mouse with soil sample.

CDC

Mechanisms permitting the survival of

Coccidioides spp. in the

host tissues

(Hung et al., 2007).

Spherule outer wall

glycoprotein (SOWgp) compromises T- cell-mediated immunity. When

SOWgp is depleted on the surfaces of endospores, host

recognition of the pathogen is prevented. The endospores induce

elevated host arginase I and also induce coccidioidal urease,

both of which contribute to local tissue damage. Arginase I

competes with inducible nitric oxide synthase in macrophages for

the common substrate, L-arginine, thereby reducing nitric oxide

(NO) production and increasing the synthesis of host ornithine

and urea.

Host-derived L-ornithine may promote pathogen growth and

proliferation by providing a pool of the monoamine, which could

be used to synthesize polyamines via metabolic pathways of the

fungal cells.

High concentrations of Coccidioides- and host-derived urea at

infection sites in the presence of urease produced by the

pathogen, results in secretion of ammonia, alkalinizing the

microenvironment. Ammonia and active urease released from

spherules during the parasitic cycle of Coccidioides increase

the severity of coccidioidal infection by compromising the

immune response to infection and by damaging host tissue at foci

of infection.

Clinical Forms

- About 60 % of infections in the endemic area are asymptomatic.

- Another 25 % of exposed people suffer a "flu-like" illness and

recover without therapy. They have typical symptoms of a

pulmonary fungal disease: anorexia, weight loss, cough, hemoptysis. The average recovery time is wks to mo. in

immune-normal people.

- About 5% of Valley Fever pneumonias result in the development

of lung nodules: small residual patches of infection appearing

as solitary lesions, typically 1 - 1.5 in diam. often with no

symptoms. On a chest x-ray, these nodules can resemble cancer.

- An additional 5% of patients develop lung cavities after an

initial infection, occurring most often in older adults, usually

without symptoms, and about 50% of cavities disappear within two

years. Occasionally, cavities rupture, causing chest pain and

difficulty breathing, requiring surgery.

- Of patients who seek medical attention 1-2% percent develop

disseminated disease; the most common site of dissemination is

the skin. Skin biopsy may reveal Coccidioides when grown in

culture.

- Bones and joints (especially knees, vertebrae, and wrists) are

frequent sites of dissemination.

- Meningitis is the most serious and potentially lethal form of

disseminated disease, with headache, vomiting, stiff neck, and

other CNS disturbances. A lumbar puncture is used to diagnose

meningitis.

Therapy

Many patients with Valley Fever pneumonia do not require

antifungal therapy because the infection is controlled by the

normal immune response. Patients who develop acute and severe

pneumonia require specific therapy. Other patients may develop

progressive pulmonary or extrapulmonary dissemination. These

latter two classes of patients both require treatment (Galgiani

et al., 2016, Galgiani and Thompson III 2016).

Factors affecting increased susceptibility include: diabetes,

advanced age, other comorbidities.

A majority of patients with complicated coccidioidomycosis have

a subacute or chronic clinical course. Initial therapy with oral

fluconazole (or itraconazole) may be necessary to continue for

months or more. Relapses may occur in approximately one-third of

patients who are apparently cured. In that event lifetime

maintenance therapy may be required. That category of patients

may have T-cell mediated immune deficiency or disease that

progressed to meningitis.

Symptomatic cavitary coccidioidal

pneumonia

Primary therapy

with fluconazole or itraconazole. A surgical option is

considered if the cavity or cavities remain symptomatic despite

antifungal treatment. A ruptured coccidioidal cavity is a

further complication. Galgiani et al., 2016 discuss the

preferred approach to surgical management of these conditions.

Coccidioidomycosis of the bones,

joints

Azole therapy is

recommended but if there is extensive or limb-threatening

skeletal or vertebral disease AmB is recommended as primary

therapy switching to long-term azole therapy after a

satisfactory clinical response. Vertebral coccidioidomycosis

warrants a surgical consultation.

Coccidioidal meningitis

Fluconazole is recommended as initial

therapy. Itraconazole may be used but requires close monitoring

to ensure adequate absorption. If patients fail initial therapy

with fluconazole, another oral azole or intrathecal amphotericin

B should be considered. Lifetime azole treatment is recommended

for this clinical form.

In rapidly progressive coccidioidomycosis, AmB is preferred as

initial treatment, stepping down to azole upon satisfactory

clinical response. Azole therapy may be needed for the lifetime

of the patient to maintain control.

Laboratory

Immunodiffusion tests

IgM react with a polysaccharide antigen

in the fungal cell wall. The IgG test reacts with a specific

chitinase enzyme. Immunodiffusion tests are considered

confirmatory of EIA test results.

Serology for coccidioidomycosis is conducted by the

coccidioidomycosis serology laboratory at the University of

California Davis, George Thompson M.D., director.

- Qualitative: Immunodiffusion (ID) to determine coccidioidal

IgM ("precipitin") (test termed “IDTP”), or IgG (CF) (test

termed “IDCF”) antibody in body fluids. This is appropriate if

no diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis has previously been

established or to confirm an EIA test result.

- Quantitative: Determination of IgG titer by complement

fixation (CF) is appropriate after a diagnosis has been made by

positive ID test or culture of the organism from patient

specimens. A positive CF test in a single specimen can be

significant. Importantly, sequential CF tests can monitor

response to therapy.

- Interpretation.

- ID tests. A positive IDTP test for IgM or IDCF for IgG. The

IgM is important in early diagnosis of acute primary

coccidioidomycosis, and is positive in most patients 1 to 2 wks

after onset of symptoms, may persist several mo. or longer when

there are pulmonary cavities or extrapulmonary dissemination.

Detecting IgM in the CSF is associated with coccidioidal

meningitis. The IDCF for IgG can be associated with recent

infection but also detectable in serum mo or yrs later.

- Complement fixation (CF). A rising serum CF titer greater than

1:16 is often associated with dissemination, but lower titers

can occur with dissemination limited to single lesions or

meningitis. A titer of greater than 1:128 usually indicates

extensive dissemination. The CF test is prognostic: A rising

titer indicating a poor response, whereas a dropping titer

reflects a favorable response.

- CF positive CSF specimens usually indicate meningitis, but IgG

can be detected in the CSF in the absence of meningitis. The CF

test of CSF may initially be negative in coccidioidal meningitis

in about 5% of patients.

- Negative serologic tests do not exclude coccidioidal disease

in some persons living with AIDS or in other immunocompromised

patients.

Enzyme linked immunoassay (EIA)

The Omega EIA (IMMY

laboratories, Norman, OK) is a qualitative serum test using two

different well strips. One is coated with a heat stable antigen

and measures the IgM response, corresponding to the classical TP

test, indicating early acute coccidioidomycosis. The second well

strip contains heat labile chitinase antigen and measures the

IgG response, the same antibodies measured in the classical CF

test. A single 1/441 dilution of patient serum is tested. The

EIA tests are read to an endpoint.

MVista® Coccidioides Quantitative Ag EIA

(MiraVista

Laboratories, Indianapolis IN) (Durkin et al., 2009). This is a

sandwich EIA that detects a heat stable antigen, a presumptive

galactomannan.

Pretreatment of serum samples with EDTA at 100°C improved the

sensitivity of detecting Coccidioides antigenemia. Antigenemia

was detected in 28.6% of patients whose samples were not EDTA-heat

treated and in 73.1% of those whose samples were treated.

Antigenuria was detected in 50% of patients. Specificity of 100%

was obtained in healthy subjects, but cross-reactions were seen

in 22.2% of patients with histoplasmosis or blastomycosis.

The MVista Coccidioides EIA was evaluated in CSF 36 patients

with coccidioidal meningitis (Kassis et al., 2015). Sensitivity

and specificity as reported were 93% and 100%, respectively.

Specificity was tested against 88 patients in the Maricopa

County, AZ health system, who had CSF abnormalities consistent

with meningitis owing to other causes. In the group with confirmed

coccidioidal meningitis, cultures of CSF were positive in 7%,

antibodies were demonstrated by complement fixation and

immunodiffusion of between 67%-70%, which increased to 85% using

an EIA to detect IgG.

.

Real-time PCR detection of Coccidioides spp.

DxNA LLC, St.

George, Utah

received FDA approval to market GeneSTAT. MDx

Coccidioides test in December 2017. This PCR based test is available for use on site in the clinical

laboratory, with a same day result. The assay is performed on

broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) or bronchial wash (BW) specimens.

The BAL/BW sample preparation includes the lysis of Coccidioides

spherules in the sample with sputolysin, then DNA extraction and

purification with the QIAGEN QIAamp DSP DNA Mini Kit. PCR of the

target sequence is done in real time. DxNA completed a

multi-center clinical study at 3 centers in AZ, and New Mexico,

also including California samples to compare the GeneSTAT Valley

Fever assay to culture of C. immitis and C. posadasii.

Direct examination and Culture of Coccidioides spp.

Clinical specimens include material from: biopsy of skin

lesions, blood, bone, brain, bronchial washings, bronchoalveolar

lavage, CSF, joints, pus from skin lesions, sputum. Viscous

mucoid sputum can be liquefied by treatment with dithiothreitol

in phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 (Hardy Diagnostics) and then

centrifuged to recover Coccidioides for direct exam and culture.

Direct Examination

For microscopy, specimens are mounted in 10% KOH with or without Calcofluor white fluorescent dye. The

Coccidioides tissue form consists of thick-walled spherules,

varying in size 30- 60 μm diam., filled with endospores (2–5 μm

diam.). Spherules with endospores are diagnostic. (see

histopathology in fig.11). Mature spherules rupture releasing

endospores which, during infection, develop into more spherules.

Conversion of the mold into the spherule form is not possible in

the clinical lab.

Fig. 11. Histopathology showing Coccidioides spherules in lung

tissue with endospores H&E stain.

Fig. 11. Histopathology showing Coccidioides spherules in lung

tissue with endospores H&E stain.

Photo credit: used with

permission from Dr. Kenneth G. Van Horn

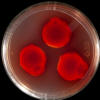

Culture

As mentioned,

C. immitis and C. posadasii are

dimorphic. (fig 6). Colonies on Sabouraud Dextrose agar

incubated at 25 o - 30o C grow in the mold form within 3-5 d,

and usually sporulate in 5-10 d. Another medium choice is Brain

Heart infusion agar. Addition of cycloheximide to the medium for

growth inhibits saprobic fungi. The highly infectious fungus can

cause laboratory infections, agar slant tubes with screw caps

are much preferred to Petri plates for primary isolation. In the

event that Petri plates are used, they should be sealed with gas

permeable tape (Shrink Seals® Scientific Device Laboratory (YouTube

video), Shrink-Seal (Remel),

or MycoSeal®, Hardy Diagnostics), and examined only in a

biological safety cabinet. Unlike bacteriologic practice,

mycologists should never sniff any fungal cultures. Because of

the infectious nature of Coccidioides species, serology or

direct exam, instead of culture, are preferred diagnostic

methods.

In culture, mycelia fragment into arthroconidia: barrel-shaped

(smaller at the edges, wider at the middle) asexual spores.

Arthroconidia alternate with non-spore-forming (“disjunctor”)

cells in the mycelium, giving rise to the term “intercalary”

arthroconidia. Fragments of the adjacent cells remain attached

to the arthroconidia giving the appearance of “wings”.

Histopathology

The inflammatory reaction is both purulent and granulomatous.

Recently released endospores evoke a polymorphonuclear response.

As endospores mature into spherules, the acute reaction is

replaced by lymphocytes, plasma cells, epithelioid cells and

giant cells. Spherules of various sizes (10 -100 µm) with many

endospores (2 to 5 µm) are hallmarks of coccidioidomycosis and

can be observed with H&E stain (fig 11). GMS stains both

spherule walls and endospores. Endospores are released into the

tissues when spherules rupture. Sometimes mycelia of

Coccidioides are found in cavitary lung or skin lesions (Guarner

and Brandt, 2011)

The inflammatory response to endospores is mainly neutrophilic,

whereas reaction to spherules is granulomatous. Early after

infection lesions are pyogranulomas because of the high

concentration of spherules and endospores . Lymphocytes cluster

around granulomas with necrosis are an important response to

coccidioidomycosis .

Eosinophils may be present leaving an eosinophilic matrix around

spherules, the Splendore-Hoeppli reaction.

Differential histopathology

Rhinosporidium seeberi, produces

large sporangia (larger than Coccidioides spherules} with

internal endospores. Endospores released from spherules or young

spherules without endospores can be mistaken for Blastomyces,

Histoplasma, Emmonsia, Candida, Pneumocystis, other yeasts. In

immunosuppressed patients Pneumocystis and Coccidioides may

occur in the same specimen.

HISTOPLASMOSIS (Histoplasma capsulatum)

Introduction

Disease Definition

Histoplasmosis is a community-acquired

pulmonary infection that, before it is contained, can spread to

organs of the mononuclear phagocytic system: bone marrow, liver,

and spleen. Fig. 12 shows yeast forms phagocytosed by a

macrophage. Hepatosplenomegaly is the primary sign in children.

The agent is Histoplasma capsulatum, occurring in soil mixed

with bird or bat feces, e.g.: blackbird roosts, chicken coops,

caves. Exposure is common in residents of the endemic area who

encounter it from disturbing the soil. The endemic area includes

states bordering the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys,

extending to eastern Canada, but is expanding as a result of

climate change, as discussed below. Most exposure is subclinical

but depending on the inhaled dose and the immune system of the

exposed person may result in pneumonia and, in a smaller group,

to extrapulmonary dissemination.

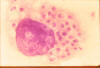

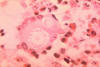

Fig. 12. Giemsa- stained tissue smear from a human case shows a

macrophage with phagocytosed H. capsulatum yeast forms.

Fig. 12. Giemsa- stained tissue smear from a human case shows a

macrophage with phagocytosed H. capsulatum yeast forms.

Source CDC,

Dr. D.T. Mc Clenan, ST69-2228

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is made from the patient’s history,

diagnostic imaging, isolation and culture of the organism, and

via serology and a commercial DNA test.

Differential Diagnosis: Tuberculosis, other bacterial

pneumonias, lung tumor (in the case of a solitary pulmonary

nodule), sarcoidosis.

Etiologic Agents

Histoplasma capsulatum is classed in the family

Ajellomycetaceae, order Onygenales, Ascomycota. Histoplasma

capsulatum is a haploid organism and has a heterothallic mating

system. In clinical samples the (-) mating type predominates.

The non-repetitive “core” Histoplasma genome is roughly 26–28 mB

encoding 9,000-10,000 genes.

H. capsulatum is divided into geographically distinct lineages,

including 6 major clades: North American class 1 (Nam1), North

American class 2 (Nam2), a Panamanian clade, Latin American

group A (LamA), Latin American group B (LamB), and an African

clade (including variety duboisii) (Edwards and Rappeleye,

2011).

Geographic Distribution - Ecologic Niche

Geographic Distribution According to an oft cited 1969 map

(Edwards et al., 1969) showing histoplasmin skin test reactivity

among Navy recruits in the U.S., the prevalence of H. capsulatum

matched states bordering the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys.

Since then change has occurred in the envi¬ronment, climate, and

human population trends (Maiga et al., 2018) (fig.13). The

advent of AIDS and of immunosuppressive therapy revealed unknown

endemic areas. Outbreaks in Montana and Nebraska led CDC to

propose that histoplasmosis is now endemic there. State

incidence rates of histoplasmosis among older persons also show

a shift in the direction of Nebraska and northern Great Lakes

regions. Surveillance from 2011- 2014 in 12 states points to

other previously unknown endemic areas in Minnesota, Wisconsin,

and Michigan.

Ecologic niche

Blackbird roosts, chicken houses and bat guano.

A patient may have spread chicken manure around his or her

garden and 3 wks later developed a pulmonary infection.

Fig. 13. State-level histoplasmosis incidence rates for 1999–2008 US

Medicare and Medicaid data (no. cases/100,000 person-years), IR,

incidence rate. Source: Maiga AW, Deppen S, Scaffidi BK, Baddley J,

Aldrich MC, Dittus RS, Grogan EL. Mapping Histoplasma capsulatum

exposure, United States 2018 Emerg Infect Dis. 24:1835-1839

Fig. 13. State-level histoplasmosis incidence rates for 1999–2008 US

Medicare and Medicaid data (no. cases/100,000 person-years), IR,

incidence rate. Source: Maiga AW, Deppen S, Scaffidi BK, Baddley J,

Aldrich MC, Dittus RS, Grogan EL. Mapping Histoplasma capsulatum

exposure, United States 2018 Emerg Infect Dis. 24:1835-1839

Image credit: Stephen Deppen, Department of Thoracic

Surgery, 609 Oxford House, 1313 21st Ave S, Nashville, TN 37232,

USA; email: steve.deppen@vanderbilt.edu

Epidemiology, Incidence and Prevalence

A summary of histoplasmosis outbreaks in the U.S.A. over the

period 1938-2013 is in Benedict and Mody 2016.

Cases of histoplasmosis are only reportable to public health

authorities in 10 states. Because of that the true incidence is

uncertain. Surveillance data for 2011–2014 from 13 states were

studied by Armstrong et al., 2018: Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware,

Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi,

Nebraska, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin. These data revealed a

total of 3,409 cases. Of these reports 1,273 (57%) patients were

hospitalized, and 76 (7%) patients died. Three states reported

cases associated with an outbreak (816 patients). Median

hospitalization stay was an estimated 7d (range 1–126 d).

Exposure to bird or bat droppings in the weeks before symptoms

developed was reported by some states. e.g.: In Michigan bird

and/or bat droppings were cited in 29% of their cases. Annual

incidence rates were highest for Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana,

Michigan, and Minnesota, ranging from 1.25 - 4 cases/100,000

population.

The extent of subclinical exposure is unknown because production

of the skin test reagent, histoplasmin, was discontinued in

2000, depriving the public health community of an important

epidemiologic tool.

Risk Groups/Factors

Anyone working a job or present at

activities where soil contaminated with H. capsulatum is

disturbed can develop histoplasmosis, depending on the number of

conidia inhaled and a person’s age and susceptibility. The

number of inhaled conidia to cause disease is unknown. Children

younger than 2 y-old, persons with weakened immune systems,

older persons, especially those with diabetes or chronic lung

disease, are at increased risk to develop symptomatic

histoplasmosis. The high-risk group also includes persons living

with AIDS, or cancer, and those receiving chemotherapy, high

dose, long-term steroid therapy or other immunosuppressive

drugs.

The proportion of hospitalizations for immune-mediated

inflammatory disease (rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel

disease, and psoriasis) listed on discharge records also

increased from 4% in 2001 to 10% in 2012, as did the proportion

with solid organ or stem cell transplant (from 1% to 6%)

(Armstrong et al., 2018).

A previous infection can provide partial immunity to reinfection.

Recreational or

occupational risk

In bat caves of Mexico and

Central America histoplasmosis is a recreational disease of cave

explorers and an occupational disease of workers who harvest bat

guano for fertilizer. Here is a summary of occupations and

recreation activity that carry an increased risk of exposure to

H. capsulatum:

- Bridge inspector or painter

- Chimney cleaner

- Construction, demolition, and maintenance workers

- Farmer

- Gardener

- Heating and air-conditioning system worker

- Microbiology lab worker

- Pest control worker

- Restorer of historic or abandoned buildings

- Roofer

- Spelunker (cave explorer)

Outbreak

An outbreak occurred in South Carolina, U.S.A. when

workers used bulldozers to clear canebrakes which served as

blackbird roosts (DiSalvo and Johnson 1979). All who were

exposed, workers and bystanders, contracted histoplasmosis. Soil

studies found viable H. capsulatum persisted at declining levels

over a 9-y period. Skin tests showed that 27.3% of 8th grade

students who resided in a 20 km radius of the contaminated site,

who were lifelong residents of the same dwelling, had a positive

histoplasmin skin test.

Transmission

Inhalation of conidia after disturbing the soil

admixed with bird or bat feces. Soils may remain a source of

infection months or years after bird roosts are gone.

Determinants of Pathogenicity

(Edwards and Rappeleye 2011)

The mold form is avirulent and preventing the mycelia to yeast

switch at 37°C blocks pathogenicity.

Several genes regulate the transition to yeast form: a kinase

Drk1; the Wor1 homolog, Ryp1; and two velvet family regulators,

Ryp2 and Ryp3. As yet, only a few genes have been proven to

contribute to virulence in vitro or in vivo.

- Cbp1. A secreted protein, the loss of which in attenuates

virulence of yeast forms in macrophage and mouse assays. Its

role is to transform phagocytes into a permissive environment

for yeast replication.

- (1,3)-α-D-glucan. Chemotype II strain walls contains α- glucan

whereas chemotype I strains lack this polysaccharide. α-glucan

production is critical to virulence of chemotype II yeast. α-glucan

promotes virulence by preventing recognition by host immune

cells. The α-glucan polysaccharide forms the outermost yeast

wall layer and conceals cell wall ß-glucans that would normally

be detected by dectin-1 receptors on macrophages.

- Yps3 is a secreted and cell wall protein with sequence

homology to an adhesin of Blastomyces dermatitidis. The Yps3

protein attaches to chitin on the G217B yeast cell wall. Yps3

(-) yeast forms are deficient in dissemination to spleen and

liver.

- Iron acquisition. H. capsulatum has more than one pathway to

acquire iron. Siderophore deficient H. capsulatum have decreased

ability to assimilate iron and display stunted growth in

macrophages and decreased virulence.

- Adhesins. Cell-surface Hsp60 is an adhesin mediating

attachment of yeast forms to complement receptors on

macrophages.

- Catalase. Hydrogen peroxide metabolizing enzymes can block or

inhibit anti-microbial reactive oxygen. The Histoplasma

M-antigen corresponds to the CatB catalase protein.

- ß-Glucosidase. The Histoplasma H-antigen is produced by all

strains, but some yeast strains release over ten times as much

ß-glucosidase activity.

Clinical Forms

Asymptomatic exposure. In the endemic area the great majority of

patients who develop histoplasmosis (95%) are asymptomatic.

Histoplasmosis generally occurs in one of three forms: acute

pulmonary, chronic pulmonary, or disseminated.

- Acute Pulmonary. There is generally complete recovery from the

acute pulmonary form (a "flu-like" illness).

- Chronic Pulmonary. Symptoms include apical cavities and

fibrosis. Persistence of the organism leads to progressive

destruction and fibrosis. This form while, uncommon or rare, is

associated with people who have underlying pulmonary disease.

- Disseminated. Patients will first notice shortness of breath

and a cough which becomes productive. The sputum may be purulent

or bloody. Patients will become anorexic, lose weight and have

night sweats. If untreated this form of disease is usually

fatal.

- Radiographic and CT findings.

Pulmonary histoplasmosis may evoke lung granulomas, causing

false-positive readings of lung tumors in radio¬graphic images

on HR- CT and positron emission tomography (FDG-PET). This means

that an increased awareness of the conditions for H. capsulatum

infection is of epidemiologic and clinical importance.

The differential diagnosis includes tuberculosis, and the chest

x- ray also looks like tuberculosis, but radiologists can

distinguish them on the chest film (histoplasmosis usually

appears as bilateral interstitial infiltrates.)

Pulmonary histoplasmosis presents a wide array radiologic

findings, which can mimic other chest diseases, e.g.: primary

lung neoplasm, bacterial pneumonia.

- Acute pulmonary: solitary or multiple nodules, lymphadenopathy,

pleural effusion (fig. 14, Solitary pulmonary nodule), (fig 15,

multiple nodules)

- Disseminated: diffuse micronodular or air-space opacities.

- Chronic cavitary: chronic upper lobe consolidation with

progressive cavitation and volume loss (seen in emphysema

patients).

- Chronic: calcified pulmonary nodules, histoplasmoma, fibrosing

mediastinitis.

Please see Semionov et al., 2019 for illustrations of the above

conditions.

Fig. 14. A 40-year-old man with a persistent nodular density in the

left lower lobe. CT scan of chest 6 mo before admission.

Fig. 14. A 40-year-old man with a persistent nodular density in the

left lower lobe. CT scan of chest 6 mo before admission.

Source: Urschel Jr, HC, Mark EJ 1988 Case records of the Massachusetts

General Hospital. Weekly Clinicopathological Exercises. Case

49-1988: N Engl J Med. 319:1530-1537

Fig. 15. Superior view of a transaxial CT scan of a patient’s

thoracic cavity, showing the classic “snowstorm” appearance of

pulmonary nodules in both lung fields, caused by the H.

capsulatum.

Fig. 15. Superior view of a transaxial CT scan of a patient’s

thoracic cavity, showing the classic “snowstorm” appearance of

pulmonary nodules in both lung fields, caused by the H.

capsulatum.

Source: CDC Public Health Image Library, #472

Therapy (for other clinical forms and dosage regimens please see

Wheat et al., 2007)

- Moderately severe to severe acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.

Lipid formulation of amphotericin B i.v. for 1–2 wks followed by

itraconazole for 12 wks.

- Mild-to-moderate acute pulmonary histoplasmosis. Antifungal

therapy is not usually necessary. Itraconazole 6–12 wks is

recommended for patients whose symptoms persist for >1 mo.

- Chronic cavitary pulmonary histoplasmosis. Itraconazole for at

least 1 y is recommended, but some prefer 18–24 mo because of

the risk of relapse.

- Pulmonary nodules (histoplasmomas). Antifungal treatment is

not recommended.

- Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis. For moderately severe

to severe disease, liposomal amphotericin B is recommended for

1–2 wks, followed by oral itraconazole for a total of at least

12 mo. For mild-to-moderate disease, itraconazole for at least

12 mo. Lifelong suppressive therapy with itraconazole may be

required in immunosuppressed patients.

Laboratory

Clinical specimens sent to the lab: Sputum, bronchial washings,

or bronchoalveolar lavage, or biopsy material from liver/spleen,

brain. Bone marrow is a very good source of the fungus, which

tends to grow in the mononuclear-phagocytic system. Peripheral

blood is also a source of histologic observation of the yeast

form is usually phagocytosed in monocytes or in PMN's (fig. 12).

An astute medical technologist performing a white blood cell

count may be the first to make a diagnosis of histoplasmosis. In

peripheral blood, H. capsulatum appears as a small yeast about

2-4 µm diam. (contrast to Blastomyces yeast forms: 12 – 15 µm

diam) Gastric washings are another source of H. capsulatum.

Fig.16 shows H. capsulatum yeast forms from an open lung biopsy.

Fig. 16. Microscopic morphology of Histoplasma capsulatum yeast

form. Open lung biopsy stained with fluorescent antibody. Ellipsoid

cells with monopolar budding are 2-4 microns/diam.

Fig. 16. Microscopic morphology of Histoplasma capsulatum yeast

form. Open lung biopsy stained with fluorescent antibody. Ellipsoid

cells with monopolar budding are 2-4 microns/diam.

Source: E. Reiss

Mycology

When it grown on Sabouraud dextrose or Mycosel agars at 25 -30

degrees C, it appears as a white, cottony mycelium after 2 to 3

wks. As the colony ages, it becomes tan. In the mold form,

Histoplasma has a very distinct conidium: the tuberculate

macroconidium (fig.17). Microconidia are also produced. The

tubercles are diagnostic, but there are some non-pathogens which

appear similar. A medical mycologist will be able to distinguish

them. Cultures on BHI + 5% sheep blood and incubated at 37 deg.

C can grow the yeast form colony. The yeast cell is 2-4 µm diam

and ellipsoid in shape. This is not diagnostic. To confirm the

diagnosis of either yeast or mold forms use the DNA probe (Accuprobe®,

Hologics. Inc.)

Fig. 17. Microscopic morphology of Histoplasma capsulatum mold form.

Tuberculate macroconidia (a) and microconidia, (b).

Fig. 17. Microscopic morphology of Histoplasma capsulatum mold form.

Tuberculate macroconidia (a) and microconidia, (b).

Source: E.

Reiss.

Serology

Serology for histoplasmosis is a little more

complicated than for other mycoses but provides more information

than blastomycosis serology. There are 4 tests: complement

fixation, immunodiffusion, EIA (antibody), EIA (antigen). The

serologic tests have different characteristics.

Complement fixation (C-F) test

The C-F test uses 2 antigens,

one from the yeast form and the other from the mycelial form.

Some patients react to only one; some react to both. C-F

antibodies develop later in the disease, about 2 to 3 mo after

onset. The C-F test cross reacts with other mycoses; it is

quantitative, and prognostic so the course of disease can be

followed with the C-F titer over time. Acute infection is

indicated by a 4-fold rise in antibody titers sera. A titer of

1:8 is positive, indicating previous exposure to H. capsulatum.

A titer of at least 1:32 or a 4-fold rise in antibody titer

indicates active infection.

Agar gel Immunodiffusion

Two immunoprecipitates may appear: the

H band is not commonly found but indicates active disease and

appears 2 to 3 wks after onset. An M band is frequent and

persistent, indicating past or present disease.

Prior to 2000 when the skin test was in use, the M-band might be

a result of a positive skin test. Skin tests also affect the C-F

titer. This interference is why skin tests are not used for

diagnosis.

Nucleic acid probe

Confirm mycelial isolates with DNA probe

recognizing ribosomal RNA, Accuprobe® Hologic, Inc., San Diego,

CA

Enzyme immunoassay

Antigen detection. Double Antibody Sandwich EIA (MiraVista

Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN). Specimens suitable for the

assay are urine, CSF, BAL, serum, plasma. Cross-reactions are

seen with blastomycosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, penicilliosis,

less in coccidioidomycosis, rarely in aspergillosis and

sporotrichosis.

Antibody detection

Indirect EIA in serum or CSF (MiraVista

Labs.) IgM and IgG versus Histoplasma antigens usually appear

during 1 mo of infection. IgM in acute pulmonary histoplasmosis

is detected in the acute phase (~3 wks) and declines in

convalescence, whereas IgG remains relatively constant at 6 wks.

Limitations are a12% cross reactivity with blastomycosis and 24%

cross reactivity with coccidioidomycosis.

Histopathology

Yeast forms are ellipsoid, 2- 4 µm diam., with a

narrow based bud. They are found phagocytosed by macrophages but

also seen in extracellularly. Gomori methenamine silver (GMS)

and periodic acid- Schiff (PAS) are the relevant stains for

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections (fig. 18).

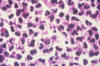

Fig. 18. Histopathology of histoplasmosis. Gomori-methenamine-silver

(GMS) stain. Yeast forms stain black with a fast green background

that does not reveal the tissue reaction. Unevenly stained, single

and budding yeast forms x 350.

Fig. 18. Histopathology of histoplasmosis. Gomori-methenamine-silver

(GMS) stain. Yeast forms stain black with a fast green background

that does not reveal the tissue reaction. Unevenly stained, single

and budding yeast forms x 350.

Source: Fig. 194 Chandler FW, Watts JC, 1987 Pathologic Diagnosis of Fungal Infections. ASCP Press.

PARACOCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS (Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, P. lutzii)

Introduction

Disease Definition

Paracoccidioidomycosis is a chronic

granulomatous disease of the lungs and mucous membranes of the

mouth endemic to Latin America. Subclinical exposure is common

in the endemic areas. Clinical forms include juvenile (subacute),

and chronic. Dissemination to the skin and visceral organs is

frequent. Regional lymph nodes are commonly involved. The

causative agents are the thermally dimorphic molds, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, and

P. lutzii.

A common triad of symptoms consists of pulmonary lesions, gum

involvement with loosening teeth, (fig. 19) and cervical

lymphadenopathy (fig. 20).

Fig. 19. Swelling of mouth and facial lesions,

paracoccidioidomycosis.

Fig. 19. Swelling of mouth and facial lesions,

paracoccidioidomycosis.

Source: Partners’ Infectious Disease Images; Accessed

on [06/14/2014] from http://www.idimages.org/ imageid=943. Case

#06010: A man from northern Brazil with respiratory symptoms and a

facial lesion. Available from: http://www.idimages.org/idreview/case/caseid=64.

Copyright Partners Healthcare System, Inc. All rights reserved

Fig. 20. Paracoccidioidomycosis, cervical lymphadenopathy.

Fig. 20. Paracoccidioidomycosis, cervical lymphadenopathy.

Source:

Dr. Arthur F. DiSalvo

Diagnosis

Paracoccidioidomycosis is diagnosed by demonstrating

P. brasiliensis in clinical samples including direct examination

and culture (please see Laboratory).Serology is a useful adjunct

and may be used to monitor the response to therapy.

- Confirmed cases: typical signs and symptoms (please see

Clinical Forms) and detection of P. brasiliensis yeast forms in

clinical samples.

- Probable: signs, symptoms and detection of antibodies in serum

by double immunodiffusion.

- Possible: Patient with at least 4 wks of cough, with or

without sputum and dyspnea, painful swallowing, hoarseness, skin

lesions, cervical or generalized lymphadenopathy. In children or

young adults with hepatosplenomegaly and/or abdominal mass.

- Differential. Paracoccidioidomycosis can often be misdiagnosed

as tuberculosis, although the two diseases can coexist.

Etiologic Agents

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis is a thermally dimorphic mold, and

a New World mycosis. It is an ascomycete classed in the

Onygenales and is genetically related to the other dimorphic

endemic mycotic agents: Histoplasma, Blastomyces, Coccidioides

species.

P. brasiliensis was considered the sole etiologic agent until

patient isolates from the central and western regions of Brazil

displayed different serologic and DNA fragment patterns leading

to the description of a separate species, P. lutzii.

Geographic Distribution/Ecologic Niche

The geographic

distribution of paracoccidioidomycosis is from mid-Mexico 20ºN

to Argentina 35ºS. Largest number of patients are from: Brazil,

Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador and Argentina. About 80% of

recorded cases have occurred in Brazil. The lack of outbreaks,

long latency period, and movement of persons outside known

endemic areas contribute to uncertainty about the ecologic niche

of infection. P. brasiliensis has a known animal host in the

endemic areas: armadillos, Dasypus novemcinctus, P. brasiliensis

is recovered from armadillo tissues. Infected armadillos imply

the presence of the fungus in the local environment, even though

isolation from the environment is rare.

Epidemiology

Incidence and Prevalence he mean number of annual

cases was estimated for the period of 1930-2012 (reviewed by

Martinez, 2017). Most cases occurred in Brazil, varying from

21.6 cases/y in the NE to 207 cases/y in the SE of the country.

By comparison, in Argentina a total of 110 cases/y were recorded

during the same multi-year period. Hospitalization rates in

Brazil were 4.3/100,000 inhabitants/year during an 8 y period

ending in 2006. Mortality rates in Brazil were estimated at 1/ 1

million population/y giving a rough approximation of 209

deaths/y.

Typically, a case of paracoccidioidomycosis in the U.S. occurs

in someone who has worked in South America for some period of

time and then returned to the U.S. The patient may not realize

the importance of the history of travel to or residence in the

endemic area. Diagnoses of fungal diseases relies on careful

questioning and a probing history.

Risk Groups/Factors

Rural workers exposed to contact with the

soil are at greatest risk. This includes farmers and, in

particular, those working with coffee or tobacco crops. Exposure

of men and women to Paracoccidioides are nearly equal, as

revealed by skin tests, but men are disproportionately affected

because ß-estradiol inhibits growth of the yeast form of P. brasiliensis. Smoking is associated with the chronic form of

this disease. Immunosuppression including HIV infection increase

the risk of this infection.

Transmission

Aerosols containing mycelial fragments or conidia

are believed to be the mode of infection. No outbreaks of

paracoccidioidomycosis are reported, and the disease is not

communicable.

Determinants of Pathogenicity

The lungs are the usual portal of

entry for Paracoccidioides sp. (Mendes et al. 2017). Conidia

reach the alveoli, germinate, and convert to the yeast form,

causing pneumonitis. Then the fungus spreads to the regional

lymph nodes evoking a granulomatous response. The immune

response then determines disease progression. A satisfactory

response blocks infection at this stage, inflammation subsides

and the fungus is eradicated or remains in a latent stage which

may last for the life of the person or, after a long time, may

reactivate, triggering disease (see chronic form, in Clinical

Forms). If the immune response is insufficient in the initial

encounter the fungi multiply and spread via the lymphatic system

and hematogenously developing into the subacute form (see

Clinical Forms).

Gp43, a 43 kDa surface glycoprotein that functions as an adhesin

has been adapted for use as a skin-test antigen, can also be

detected in serum during infection. Some strains of P. brasiliensis do not express the antigen. Gp43 is not entirely

specific because the carbohydrate chains in gp43 cross react

with serum from patients with histoplasmosis and lacaziosis.

Gp43 enhances pathogenicity by inhibiting phagocytosis and

intracellular killing (Camacho and Niño-Vega 2017). Gp43

strongly induces in vitro granuloma-like formation by

macrophages. In the case of P. lutzii, a gp43 ortholog, “Plp43”,

shares only few epitopes in common; thus gp43 should not be used

in the diagnosis of patients infected with P. lutzii

α- 13- D-glucan is expressed in the yeast form. It enhances

pathogenicity by masking recognition of the major cell wall

polysaccharide: ß-13- D-glucan by the dectin-1 receptor of

macrophages. Dectin-1 is a pattern recognition receptor that

recognizes ß-glucan, triggering phagocytosis and downstream

release of cytokines.

The enlarged multi-budding yeast form of

Paracoccidioides

physically impairs phagocytosis.

Clinical Forms (Shankar et al., 2011)

Subclinical Positive skin test reactivity to paracoccidioidin or

serologic tests (anti gp43 antibodies) detected previous

subclinical infections in a significant proportion of healthy

individuals in various endemic countries (Martinez 2017). This

primary exposure is usually self-limited. Paracoccidioidomycosis

disease is thus regarded as affecting a small minority of

exposed infected individuals.

Juvenile

Children, adolescents, young adults (under 30 y-old).

In a sub-acute form there is lymph node enlargement, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and it may disseminate including

skin lesions, osteoarticular involvement. Rarely progresses to

chronic form. May reactivate years later.

Chronic

Seen in adults over 30 y-old, may result from

reactivation of quiescent lesions. The chronic pulmonary form

may be mild to severe. Disease progression is slow. Without

treatment, the severe form may ensue: Painful lesions on the

mucous membranes of mouth, lips, gums, and on the skin. There is

wt loss, lymphadenopathy that may be suppurative, with frequent

adrenal gland, CNS, and bone involvement. Men comprise more than

90% of those afflicted with this form of paracoccidioidomycosis.

A proposed reason for this is that form development from the

mold to the yeast form is inhibited by estrogen (Shankar et al,

2011).

Oropharyngeal lesions are the result of dissemination from a

pulmonary focus of infection affecting the mucous membranes of

the mouth, loosening teeth resulting in their loss. White

plaques are found in the buccal mucosae, and this along with the

triad are now used to clinically differentiate between TB and

paracoccidioidomycosis. Other sites of dissemination include

skin and internal organs. An important feature of the

disease is a long latent period. Ten to twenty years may pass between infection and

emergence of the disease, sometimes in non-endemic areas of the

world.

Therapy

Itraconazole and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are the

choices for primary therapy with similar effectiveness. The time

to reach clinical cure is shorter with itraconazole, including

those patients with the chronic clinical form.

Laboratory

Specimens to send to the lab: Sputum, lower respiratory tract

secretions, bone marrow, biopsy material from liver or spleen,

pus and crust from lesions on skin and mucous membranes, pus

from draining lymph nodes.

Direct microscopic examination: Microscopic exam of sputum or

crust from a lesions is done by first adding a drop of 10% KOH.

Identification of P. brasiliensis in sputum is more difficult

than in skin scrapings and lymph node specimens. When sputum is

clarified with 10% KOH and then homogenized yields are higher

than only using cleared sputum.

Tissue specimens may be cut with a razor blade or homogenized

and examined microscopically before seeding to culture medium.

Microscopy reveals the yeast form which, in contrast to other

fungal pathogens, displays multipolar budding, a thin cell wall,

and a narrow base bud: the so-called “mariner’s wheel”. Yeast

forms vary from 2-30 µm diam. Strains also vary in that the

mother cell may be similar in size to the daughter cells or much

larger.

Culture

P. brasiliensis mold form is cultured on Mycosel or

Mycobiotic Agar, SABHI (Difco), Sabouraud agar or yeast extract

agar. Medium with cycloheximide is permissive for mold form

growth but inhibits the yeast form. Sputum samples are

pre-digested with pancreatin or N-acetyl-L-cysteine. Incubation

is at room temperature. Growth of the mold form is very slow and

may take 15-20 d before growth is visible.

At 25 degrees C, the colony is a dense, white mycelium not loose and

cottony .On Sabouraud dextrose agar it may take 2-3 wks to grow.

Note: the Blastomyces Accuprobe®, Hologics, Inc. gives a

positive reaction with P. brasiliensis and may be used in the

diagnostic work-up.

Since sporulation is scarce, conversion to the yeast form is an

important part of the lab diagnosis. This is done on agar slants

containing brain-heart infusion or Kelley agars, incubated at

35-36ºC. The yeast form is also slow growing into a white-tan,

thick colony.

Histopathology

Biopsied tissue specimens are formalin-fixed,

paraffin-embedded, then stained with either or both H&E and Gomori methenamine silver. H&E staining shows the host

inflammatory response, granuloma formation, and Paracoccidioides

sp. yeast forms (fig.21). GMS stains the fungus wall showing the

typical yeast forms with multipolar buds, but not the

inflammatory response (fig. 22).

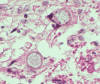

Fig. 21. Histopathology of a skin tissue sample in a case of

paracoccidioidomycosis. A budding yeast form of Paracoccidioides

brasiliensis is phagocytosed by a multinucleate giant cell.

Fig. 21. Histopathology of a skin tissue sample in a case of

paracoccidioidomycosis. A budding yeast form of Paracoccidioides

brasiliensis is phagocytosed by a multinucleate giant cell.

Source.

Image #522 Dr. Lucille K. George, CDC Public Health Image Library.

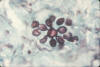

Fig. 22. Photomicrograph of a Gomori methenamine silver stained

unidentified tissue sample, shows the yeast form of Paracoccidioides

brasiliensis, in a case of paracoccidioidomycosis. The multipolar

budding yeast form resembles what has been referred to as mariner’s

wheel.

Fig. 22. Photomicrograph of a Gomori methenamine silver stained

unidentified tissue sample, shows the yeast form of Paracoccidioides

brasiliensis, in a case of paracoccidioidomycosis. The multipolar

budding yeast form resembles what has been referred to as mariner’s

wheel.

Source: #498 CDC Public Health Image Library

Serology

Detection of antibodies by agar gel diffusion is the

main test for diagnosis. Accuracy is high and results correlate

with response to therapy. Antigens used are (1) yeast-phase cell

culture filtrate antigen and (2) supernatant from sonicated cell

suspensions. Sensitivity is estimated to be 77%, and

specificity, 95%.

Endpoint serum dilution titers indicate severity of disease and

subside in response to therapy. P. brasiliensis 43-kDa

glycoprotein (gp43) is significant in the immune response in PCM

but some P. brasiliensis isolates do not express gp43.The

identification of different species - P. brasiliensis and

P. lutzii and P. brasiliensis cryptic species suggests that

antigens be prepared from the dominant species in a particular

region.

ELISA can detect very low antibody concentrations with